About the LTN for Hanover and Tarner

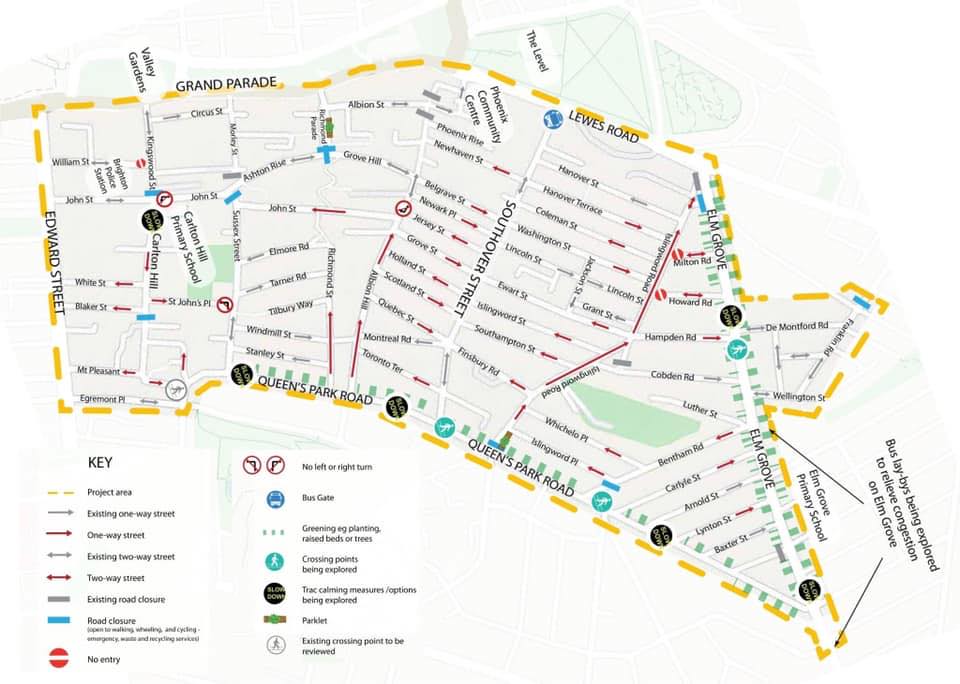

The map below shows the current plan for the Low Traffic Neighbourhood scheme in Hanover and Tarner, planned implementation in 2023. Most entrance and exits to the area will be blocked off. The main access route will be through the top of Southover Street, where traffic can travel both ways. There are a couple of additional one way entrances and exits as shown.

We are aware that this plan has now been described as ‘unfit for purpose’ by BHCC, the people that commissioned and paid for it. A completely new plan has been designed but we are not currently being given access to this. A recent letter from Councillor Elaine Hills says that it will be available to view sometime in February (the latest of many promises), so probably a matter of weeks before the LTN is approved in March. There will be no opportunity for residents to comment on or ask for changes to this new version. In our view this makes the whole consultation invalid.

* Update March 2023 -We have still not been shown any new plans. The LTN has now been taken off the agenda for the March 17th ETSC meeting, so no decision will be taken until after the May local elections.

There is a Q&A list on this page, talking about some of the main points. It’s not comprehensive, some of it is personal opinion and other parts may need correcting, especially as the situation changes. You can send suggestions and comments to admin@stophanoverltn.org.uk

To explore the plan in more detail and join the discussion, please visit the ‘Stop or improve the Hanover and Tarner LTN’ Facebook page.

- Who is asking for an LTN in Hanover?

- What is the purpose of the LTN?

- Why is the LTN referred to as a ‘Liveable Neighbourhood’?

- Have residents and businesses been consulted?

- Have residents been given the opportunity to reject the LTN?

- Have LTNs been successful in other areas?

- What will happen in Boundary Roads?

- Why are BHCC and the Green Party supporting it?

Who is asking for an LTN in Hanover and Tarner?

The Hanover and Tarner LTN was the idea of a small group of six people from the local Hanover Action Group, headed by local Green councillor Elaine Hills. In 2020 they took a deputation to BHCC, who decided to promote it. It does not appear to have popular support. Residents are being denied a Yes/No vote so this is difficult to assess.

Our three Green councillors, David Gibson, Steph Powell and Elaine Hills, all support the LTN. Of these councillors David Gibson is a resident, Steph Powell lives outside the area and Elaine Hills is moving to Preston Park, so will not be experiencing any of the effects of an LTN in Hanover herself.

Elaine Hills is also co-chair of the ETS committee which will decide whether to go ahead with the LTN. This seems like an obvious conflict of interest. Ms Hills has referred herself to to the council legal team on this matter. We believe it’s unethical for her to remain as co-chair, a legal opinion is superfluous, and she should step down immediately.

Low Traffic Neighbourhoods - controversial and often unpopular with residents

What is the purpose of the LTN?

As described by local Green councillor Steph Powell, the purpose of the LTN is to ‘eliminate rat running – calm/reduce speeding traffic and anti social driving – reduce emissions from transport as part of the BHCC de-carbonisation program – increase active travel (walking, cycling etc.) – improve public health and incentivise people to walk and cycle to improve mental and physical health outcomes’.

The list can vary, depending on which councillors or council officers you talk to. These are all things that are hard to argue with, but we believe that an LTN is not going to achieve these objectives and will in fact: increase pollution, make local journeys very much longer, cause problems in boundary roads (such as Elm Grove and Queens Park Road) and seriously damage local businesses.

Hanover does not appear to be a high traffic area, apart from some busy periods during the mornings and evenings. Southover Street and Islingword Road have a steady flow of cars but the average side street is quiet for most of the time.

Why is the LTN referred to as a 'Liveable Neighbourhood'?

Possibly because it’s easier to promote than LTNs, which have had some very bad publicity recently. It’s quite hard to say that you don’t want a Liveable Neighbourhood without sounding unreasonable. The terminology can bias discussions and make it difficult to explain what is actually being proposed. Councillors have been challenged on this and continue to use misleading language.

In this case ‘Liveable Neighbourhood’ means ‘Low Traffic Neighbourhood’

Have residents and businesses been consulted?

BHCC ran a consultation in 2022, this consisted of drop in sessions and and an online questionnaire. Many residents have complained that this was not a valid consultation. During the drop in sessions, council officers seemed unwilling to discuss changes and were not offering an option to reject the idea of an LTN altogether. Officers took no notes when speaking to residents, so it’s hard to see how they were taking any objections or suggestions seriously. The online questionnaire was extremely limited, was full of leading questions and gave no chance to express doubts about the scheme. There was no feedback from the consultations, apart from an admission that the whole plan was not fit for purpose.

Despite the complete failure of the first plan, a second plan is now being devised. Residents have not been allowed to see the new proposals. We are not being allowed to comment or object before the final decision whether to go ahead is made in the ETS Committee meeting in March.

We are asking to see the new plan and ask for changes well before the ETSC. We also want an option to reject it altogether. Green councillors repeatedly tell us that residents are overwhelmingly in favour of an LTN, in which case why don’t they ask us? It would be a simple thing to do.

e

Have residents been given the opportunity to reject the LTN?

Councillors have decided that saying No to the LTN is not an option, so residents have not been allowed to say No.

Have LTNs been successful in other areas?

LTNs have been controversial wherever they have been introduced. Reliable data is hard to find but it seems like over a third have already been removed. There are protests and pressure groups campaigning for the removal of others throughout the UK.

7 LTNs have been scrapped in Ealing. The objectives of reducing air pollution were not met. A council report concluded that problems were generally displaced to boundary roads. In Ealing at least, between 63 and 79 per cent of those living inside the schemes were opposed to them, rising to 67 to 92 per cent among those living on the boundaries.

LTNs based on false data removed

Oxford residents have started legal proceeding to remove LTNs in their area

The Department of Transport has admitted that LTNs have been based on incorrect data

The BBC’s ‘More or Less’ radio show also questions the data behind the introduction of LTNs, the article is towards the end of the show.

What will happen in boundary roads and areas

If an LTN is introduced, traffic and pollution will increase. It’s inevitable, despite denials by the council and Green councillors. This is of huge concern to residents of Elm Grove and Queens Park Road. The bottom of Elm Grove in particular already exceeds legal nitrogen dioxide limits and this will make it worse, with longer traffic jams backing up from Lewes Road. Data from other areas has shown that pollution and traffic are not usually reduced by an LTN, they are just displaced. Longer journeys in and out of Hanover will be displaced to these boundaries. These roads already have problems with road safety, especially around Elm Grove Primary School. Residents in Queens Park have started their own Facebook group to try and highlight the problems.

We are 100% behind much needed improvements in these roads, whether an LTN goes ahead or not. We do not think the LTN and improvements to surrounding roads should be interdependent.

You can ask to join the group here:

Why are BHCC and the Green Party supporting the LTN?

Probably a combination of reasons. For some people it’s a sincerely held, but we think mistaken, belief that it will help achieve climate change targets and reduce pollution. Others seem to be driven by ideology and are not interested in the realities of the situation.

We believe that Hanover and Tarner is particularly unsuited to an LTN. Being near the city centre means that most residents will already walk or take a bus into town if at all possible, so there is not a big problem with cars being used for short journeys. It’s situated on one of the steepest hills in the area, making proposed greater use of bicycles and walking difficult for older and disabled residents who may need to use cars.

The Labour Party have recently announced that they will not be supporting an LTN in Hanover. They also voted with the Conservatives to defund the LTN and re-allocate funds towards refurbishing toilets in the city.

Will the LTN reduce air pollution and traffic

It’s very unlikely. Journey times will increase greatly due to longer routes in and out of the area. An example of a two way car journey from Hanover Terrace at the lower end of Hanover to Lewes Road:

Before LTN, drive to end of road, left into Islingword Road, join the end of Elm Grove at the traffic lights, turn left or right into Lewes Road. Journey time one way less than 1 minute, distance for a return journey: 0.4km or 1/4 mile

After LTN, drive to end of road, turn left into Islingword Road, left into Hanover Street, at end of road turn left into Southover Street, at top of Southover Street turn left into Queens Park Road, at end of Queens Park Road turn left into Elm Grove, drive to the end of Elm Grove, at the traffic lights, turn left or right into Lewes Road. Journey time one way up to 10 minutes, depending on newly created traffic jams on Elm Grove, distance for a return journey: 3.8 km or 2.4 mile.

That’s an 850% increase in journey length, with corresponding increases in energy use and pollution.

BHCC says that they expect people to use cars less after the introduction of the LTN. Even if there is a massive decrease in car journeys, the extra mileage will still more than cancel out any possible benefits.

How is the LTN going to be financed?

BHCC are using £300,000 for the LTN itself and £1.1 million for improvements to boundary roads. The money will come from Capital Funding loans, so will be funded by local council taxes. The scheme will also need ongoing funds to maintain it, these are likely to come from traffic penalty fines. Plans include installation of a Bus Gate and ANPR (automatic number plate recognition) cameras to generate income. One Green councillor has said that there is nothing to worry about, as the fines generated by the scheme will more than cover the costs of maintenance.

We were initially told that the two schemes were separate, and then more recently that they are interdependent, i.e. we can’t have one without the other. This is important. Residents in surrounding roads are being told they won’t get improvements unless we accept an LTN, many residents within Hanover and Tarner would like surrounding roads to get their improvements but don’t want an LTN. It puts our community in conflict.

There will also be a financial problem if the scheme is judged to be a failure and needs to be removed, there are no funds allocated to cover the cost of dismantling the scheme. It makes it less likely that it will ever be removed, regardless of local opinion, after the ‘trial period’. In a failed scheme in Brent, the local council is having to find money out of existing budgets to remove an LTN at an estimated cost of £20,000.

How will fines and penalties be raised and enforced?

According to the original plan there would be a Bus Gate at the bottom of Southover Street, cars will be fined if they use this route during operational hours. Enforcement will be through new ANPR cameras installed in the area, cameras will also be installed at the ends of Milton Road and Howard Road. Operational times and conditions are going to be quite unclear for anyone unfamiliar with the restrictions, a financial trap for the unwary.

The new and yet unconfirmed plan appears to show the Bus Gate moved to the middle of Southover Street, creating additional problems.

Two other bus gates in Brighton generated 2.2 million pounds in fines in one year. This will generate a lot of money for BHCC and contractors, and is possibly one of the main incentives for introducing an LTN in the first place.

Who decides if the LTN goes ahead

Councillors on the ETSC (Environment, Transport & Sustainablity Committee) at Brighton and Hove City Council will make the decision whether to go ahead with the LTN. This has been changed several times and is currently scheduled for March 17th 2023. This meeting will be co-chaired by one of the main proponents of the LTN, Elaine Hills.

* Update March 2023 – No revised plans have been produced, despite many promises, and the LTN has now been taken off the agenda for the March 17th ETSC meeting. This does not mean that the LTN plan has been dropped but no decision can now be made until after the May elections.

* The BHCC legal team have also ruled that Cllr Hills has a conflict of interests, so she will no longer co-chair the meeting.

Is the decision to go ahead with the LTN final?

At the ETS commitee meeting in June 2022 the decision to consult on the design of an LTN was passed with a view to it being implemented as soon as a final design is reached. There is no intention to consult with residents about this final plan. On implementation the LTN enters an 18 month trial period. In theory the LTN could be removed at the end of the period, but this seems unlikely for financial and political reasons. The general feeling is, if it’s implemented we’ll be stuck with it.

The trial is also being called ‘further consultation’.

Is Hanover a high traffic area?

No, Department of Transport pollution mapping shows that Hanover and Tarner themselves have relatively low emissions (i.e. traffic) but boundary roads, in particular Elm Grove and Lewes Road already exceed UK nitrogen oxide limits. Currently all small H&T side roads have limited through traffic. Vehicles can enter and exit the area easily without the long and uneccessary diversions that will be caused by an LTN.

A short walk around the area on a typical day will confirm that there is no huge problem with traffic here. There are cars around, and some of the main routes get busy in the morning and evening but side roads are generally quiet and safe.

Is this group full of climate change deniers?

No, conversations with members of the group show that we are fully aware of the dangers of climate change. We take our own steps to reduce our carbon footprints and are prepared to make major changes to our lifestyles. What we are not willing to do is to be forced to follow an ideology that will damage the area without fixing the problems. This LTN does not make sense from an environmental, business or social point of view. Until it is changed or dropped altogether there will be continuing resistance from residents.

The council could implement some changes that would be helpful without forcing an LTN. A better bus service would encourage people to leave cars at home. At the moment the service is infrequent, expensive and often unreliable.

Electric car charging points and parking bays would encourage the changeover from diesel and petrol. Combined with a renewable energy system backed by central government this would make a huge difference.

Grants for home insulation would reduce CO2 emissions locally. It’s a very cost efficient, well proven way to reduce energy use.

Log burners are in common use in the area, unsurprising considering the current cost of energy, but these are huge polluters. Even wood-burning stoves meeting the new “ecodesign” standard still emit 750 times more particle pollution than a modern HGV truck. If BHCC are serious about improving air quality, this is something that could be discussed.

The Times view on LTNs - published 25/10/22

“The aim was laudable. As Covid tightened its grip on the country, councils in London began installing bollards, gates and flower tubs to block off residential neighbourhoods to through traffic. Cars and taxis using rat-runs to avoid congestion were forced back on to the main roads. Flaunting their commitment to the environment, council leaders promised less pollution, safer side-streets, new cycle lanes and quieter walks to shops and schools. Low traffic neighbourhoods (LTNs) were a bold experiment in urban planning. They have proved an expensive and infuriating failure.

The government has spent more than £300 million in grants to reroute traffic away from residential streets. Most of the schemes were implemented at the height of the pandemic, with little consultation and in the hope that they would lead to a permanent reduction in car use. But since then there has been little monitoring of traffic flows, little attempt to quantify the reduction in carbon emissions and refusals to address the avalanche of complaints by motorists caught up in lengthy traffic jams or households facing longer journeys.

An investigation by The Times has now found that many of the trumpeted advantages are illusory. Traffic did not go down in the 10 London boroughs that have introduced LTNs in 2020; it rose by an average of 41 million miles or 11.4 per cent as traffic came back after the first lockdown. By contrast, the two inner London boroughs that did not implement the scheme saw a rebound of only 29 million miles or 8.9 per cent. While these figures do not prove the LTNs are causing the extra miles, it suggests the schemes may not be as green as their promoters suggest: cars caught in jams or having to take longer journeys emit thousands of tonnes more carbon dioxide.

Data also shows that traffic on minor London roads did not rise by almost 60 per cent between 2009 and 2019, as LTN advocates claimed, but instead there was virtually no change in volumes over the decade. Indeed, in those boroughs that introduced the schemes traffic was already in perceptible decline.

Much is made by campaigners of the improvement in air quality and lifestyle for those living in inner cities. But these improvements are mostly in richer, leafy neighbourhoods. And on the boundary roads, suffering a huge increase in traffic volumes, poorer households often suffer much more pollution. Nor do these changes encourage people to switch to public transport. Buses can take longer to plough through congestion, and as a result are less attractive.

One result of introducing LTNs with scant consultation is that little thought has been given to access by emergency service vehicles or to the added pollution affecting schools situated on main roads. Instead, the emphasis has been on how much cycling would be encouraged with safer roads and new cycle lanes. This does not depend on LTNs. Cycle lanes are being successfully introduced without the need to fence off neighbourhoods. Cyclists can, and should, be encouraged — but will hardly be attracted to main roads now choked with fumes and traffic.

What is now needed is for councils to listen to the complaints and rethink hastily imposed schemes. Some roads should be unblocked; some barriers should stay. Not all motorists are rich and selfish; and closing streets is not the only or best way to cut carbon emissions in our cities.”